Preston Yancey’s Tables in the Wilderness and the Uprooting of My Denominationalism

I’m blessed in that I often get the jump on new books before they hit stores, thanks to my job. I’ve just finished one that I really want to share with you – and there’s a little something special available at the end, too. So read on, dear ones.

I’m blessed in that I often get the jump on new books before they hit stores, thanks to my job. I’ve just finished one that I really want to share with you – and there’s a little something special available at the end, too. So read on, dear ones.Preston Yancey (no relation to the esteemed Philip Yancey, oddly enough) is an old soul of sorts, and yet he’s also very young – at heart, in humor, and in his ability to share openly and honestly, without rancor, the religious tension of his college years. Born into the Southern Baptist tradition, Preston found himself at Baylor University at 18, questioning the “best place for [him]” within the Christian faith. He eventually found it in the time-steeped traditions of the Anglican church.

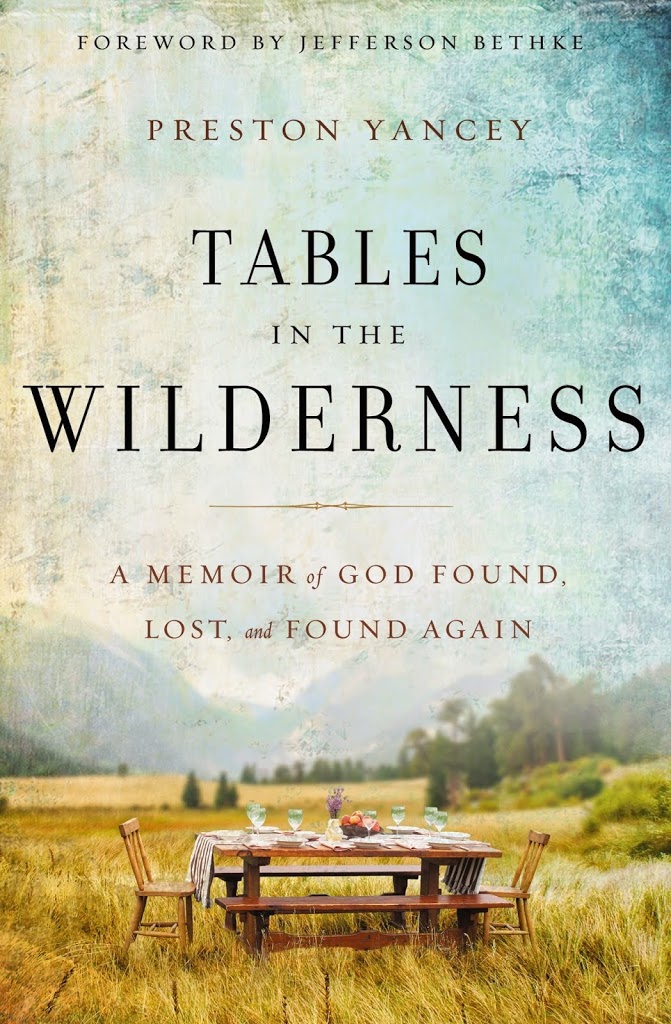

Tables in the Wilderness is a memoir of that journey. During the season we are invited into in Tables, Preston ceases to be able to “hear” God in the way he has always been accustomed, and therefore feels as though he has entered a wilderness of uncertainty. Rather than shaking his faith in God, this shakes his sense of his own worthiness to hear from God. Eventually, he is able to see that God never left him, that He actually built tables in the wilderness of His silence where Preston sat down and feasted with friends – on knowledge, on wisdom, on the deeper things of the Spirit.

The tables, clearly, are a metaphor for God’s rich and sometimes mysterious provision, which often eludes human comprehension until long after a life season has ended. This can be seen repeatedly in the Bible and in Christian writings through the ages, from people of all traditions within the faith. Tables offers encouragement for anyone who is in a season that feels like a spiritual wilderness – encouragement to look for the table and the feast God has laid out.

For me, personally, God used Preston’s memoir to do something additional. Throughout Tables, he and the people in his life wrestle with denominational differences. They debate, they invite, they seek and explore. Preston finds himself attending two church services every week – the Baptist church of his upbringing, and the Episcopalian church, where he is drawn to the scripted beauty and comfort of the traditional liturgical service. Eventually, he finds himself drawn even more deeply to the Anglican church, which he joins years later.

What struck me most deeply was how he articulated his explorations as being about finding “the best place for [him],” the place where worship felt the most meaningful. It wasn’t – isn’t – about the “rightness” or righteousness or correctness of a denomination’s ways of doing church. It is simply about what feels best to the person in the pew or chair, about which environment engenders closeness to God.

I confess, I have wrestled with denominationalism, although without fully realizing it. And . . . I believe I have harbored some prejudices. Deep down, I have had a deep-seated suspicion that churches that are not my “best place” were somehow not doing Christianity “right.” I have always spoken from a denomationalist perspective, saying things like, “The church will be united in heaven, and it’s okay that we are not united now, even though that was Christ’s vision, because we live in a broken world, yada yada . . .” In all honesty, those were somewhat empty words – there was a part of me that believed that my church(es) was, in fact, “doing it right.” That it was the other denominations who were somehow the problem behind church disunity. Of course, that’s not true.

I think my prejudice began when my sister was confirmed in the Catholic church as a teenager, long before she “defected” to a non-denominational church. I attended the service, and I remember vividly that there was a notice pasted inside the front cover of the hymnal that stated that anyone who was not Catholic should abstain from taking Communion, regardless of denomination. I remember being furiously affronted that my [non-Catholic] belief in Christ as my savior made me unworthy of Communion in the eyes of the Catholic church (or, at least, in that particular church). I took Communion anyway – admittedly not with the right motivation that day!

Tables in the Wilderness nudged at my skewed denominationalism. I can’t describe what I was feeling as I was reading – the best thing I can come up with is a sense of something being uprooted and drawn out of me. I was taken back to when I read Lauren Winner‘s Girl Meets God, about a decade ago. I remember that Lauren’s writing made me feel drawn to both traditional Judaism and to liturgical Christianity, for their beauty and tradition, for their depth and mystery. After reading Girl Meets God, my faith felt broader somehow. Tables in the Wilderness had a similar effect. And this time, it felt like there was nudge from God in it – like He’s somehow telling me I need to really, truly see the church as a unified body even with all its fragmentedness. I don’t know why this nudge is happening to me now, or for what purpose, but I’m tuning my ear, listening for more.

Friends, Tables in the Wilderness is a lovely, stirring, inciting book. It both satisfied me and made me thirstier for God. Right now, it’s available for pre-order, and if you do, you get something extra-special: a collection of delectable recipes from Preston, who claims he might have been a food writer in another life. The collection – four starters, three main dishes, three desserts – is designed to encourage you to form a table of your own – in the wilderness or not – and invite others to surround it. It’s the loveliest kind of freebie – something that incites creativity and hospitality and discourse between friends. So go – order yourself a copy, and then plan a dinner party around your own table.

4 thoughts on “Preston Yancey’s Tables in the Wilderness and the Uprooting of My Denominationalism”

Comments are closed.

Thanks for sharing this.

Thanks for reading! 🙂

This is such a kind review and means the world to me. Truly. Thank you.

It was a joy and a delight! Truly, my pleasure. 🙂